- Home

- Kurt Tucholsky

Castle Gripsholm Page 10

Castle Gripsholm Read online

Page 10

‘Smoke your pipe!’ said Karlchen. ‘Go on, smoke it! He can’t take nicotine, Princess! Is it a new pipe?’

‘That’s the trouble,’ I said, ‘I have to break it in . . .’

‘Aren’t there machines for that?’ asked the Princess. ‘I’ve heard of something like that.’

‘Yes, there are,’ said Karlchen. ‘I had a friend at school who discovered a way of using an air-pump to break in a pipe. I can’t remember how he did it – but he did. I gave him my new pipe, a wonderful new pipe. And he must have pumped at it a bit too strongly . . . and the pipe smoked itself, and there was nothing left of it but a little pile of ashes. He had to buy me a new one. That story always seemed very symbolic to me . . . Yes, but I forget what it symbolised.’ We remained silent, lost in thought.

‘An ass!’ said the Princess. We wanted to protest, but she was referring to a real one, which had just appeared from behind some trees. He was probably after some whisky too. We got up at once and stroked him, but asses don’t like being stroked; a wise man discovered that it was their misfortune to be called asses, and that was the only reason why they were so badly treated. We treated this one well and called him Joachim. We played the gramophone for him . . .

‘Play a bit from Carmen,’ said the Princess. ‘No! Play the one with the little gnomes . . .!’ That was a piece of music with a little skipping-marching rhythm, and the Princess insisted it was meant to go with a pantomime in which dwarves with little lanterns scampered across the stage. I put on the record with the gnomes, the machine did its stuff, the ass ate grass and we drank whisky.

‘Another finger for me please!’ said Karlchen.

For dessert the Princess was eating celery and cheese, as a great gourmet had recommended.

‘What’s it like?’ asked Karlchen.

‘It tastes,’ the Princess chewed slowly and thoughtfully – ‘it tastes like dirty laundry.’ Even Joachim swished his tail about in disapproval.

Then we sang him all the songs we knew, and there were a considerable number of them.

‘King Solomon has three hundred wives

and that’s the reason why

he always missed his morning train

kissing them all good-bye!’

‘Mooh!’ went the ass, and was given a talking to – after all, he wasn’t a cow. Karlchen blew some gentle melodies on a comb-and-tissue-paper, and boisterously expressed a desire to go to the Chantant . . . the Princess laughed a lot, and sometimes at an undignified volume, and, like both of the others, I was convinced I was the only one left sober in the midst of this hullaballoo.

Before we went to bed, I said, ‘Lydia – he’s not to write postcards this time! He keeps writing postcards!’

‘What kind . . .?’ she asked.

‘When he leaves, the craziest postcards arrive the next day, he writes them on the train. It’s his way of saying goodbye. He’s not to; it worries me!’

‘Herr Karlchen, will you swear not to write any postcards?’

He gave us his word of honour as a citizen of Giessen. We hit the sack.

The next evening we took him to the station, to the little puffing railway train, and the two of them gave each other a farewell kiss that seemed to me to take rather a long time. Then he had to get on, and we stood beside the little carriage, giving him good advice for the journey. He bared his teeth at us and when the train started to move, he said agreeably, ‘Fritzchen, I’ve taken your toothpaste with me!’ In my excitement I threw my hat after him, and it almost rolled under the wheels. He waved, and then the little train disappeared round the corner, and we couldn’t see anything any more.

At noon the next day, four postcards arrived: one from each of the main stations on the way to Stockholm. On the last one he had written the following:

‘Dear Toni!

On no account let the police take you in for questioning over the false entry at the hotel on the 15th! If need be, remain firm and insist you are my daughter!

Dear friend, before I left this evening, I looked at your profile once more and I must say I was seriously alarmed. I believe you’re losing your hair. That’s more than an indication – that’s a symptom!

Don’t search in vain for the second canary – I’ve taken it home for my dear little children. Where is the ass?

Dear Marie, please look at once for my signet-ring – it must be under your pillow. I know it for a fact.

Pity about my wasted holiday!

I am evermore

your dear

Karlchen.’

Chapter Four

So long as our pastor doesn’t see me,

I’ll take my chances with God, said the peasant –

and he made his hay on a Sunday.

1

‘How did all that come about so suddenly?’ asked the Princess, as I toppled out of my head-stand.

We were doing exercises, Lydia was, I was – and over there, Billie was rolling about under the trees. Billie wasn’t a man, but a young woman by the name of Sibylle.

‘Oh boy . . .’ said the Princess and dropped onto the ground, gasping for breath. ‘If that doesn’t make us clever and beautiful . . .’

‘And slim,’ I said, and sat down next to her.

‘How do you like her?’ asked the Princess, with a nod over at the trees.

‘I like her,’ I said. ‘She’s a nice girl: fun, playful, serious when she wants to be. Such a sweetheart!’

‘Who?’

‘Her.’

‘Talking of hearts, Poppa, she’s just broken up with her boyfriend, but discreetly and amicably.’

‘And who was he again?’

‘The painter. A decent young man. It just didn’t work any more. Don’t ask her, she doesn’t want to talk about it. It’s the kind of thing you have to cope with on your own.’

‘How long have you known each other?’

‘Oh, ten years and more. Billie . . . she’s like Karlchen to me, you know? I like her. And a man has never come between us. I just can’t imagine that ever happening. Look at her, the way she runs! As if her pants are on fire!’

Sibylle came over.

I liked watching her run; she had long legs, a firm torso, and her dark-blue swimsuit glowed against the green of the grass.

‘Well, you monkeys?’ said Billie and sat down with us. ‘How was it?’

‘Profitable,’ said the Princess. ‘Fatty here did some exercises, his knees will be coming through the back of his neck any minute . . . he’s been very good. How long have you been skipping now?’

‘Three minutes,’ I said very proudly. ‘How did you sleep, Miss Billie?’

‘Quite well. At first, when the woman got the small room ready for us, I thought it might be too hot, with the sun shining in there all day, but it wasn’t really that hot at all. So I slept quite well.’

We all looked attentively ahead, and swayed to and fro.

‘It’s great that you’ve come,’ said the Princess, and tickled the back of Billie’s neck very gently with a long blade of grass. ‘We were going to live here like a couple of hermits–but then first his friend Karlchen arrived, and now you – but it’s so quiet and peaceful . . . no, honestly . . .’

‘How kind of you Ma’am,’ said Billie and laughed.

I loved her laugh; sometimes it was silvery, but sometimes there was a dovelike quality about it – a cooing laugh.

‘What a pretty ring, Billie,’ I said.

‘It’s nothing . . . a little everyday ring . . .’

‘Show me . . . an opal? Opals . . . you know . . . opals are unlucky!’

‘Not for me, Herr Peter, not for me. Should I wear a diamond instead?’

‘Of course you should. And then you can use it to scratch your name in the mirror of your chambre séparée. That’s what all great cocottes do.’

‘Thanks. By the way, Walter said he’d been in a cabinet particulier in Paris too, and someone had scratched something on the mirror there. Guess what it said

!’

‘Well?’

‘Vive l’anarchie! I thought that was great.’ We were pleased.

‘Shall we gymnase a bit more?’ I asked.

‘Not for me, thanks,’ said the Princess and stretched. ‘I’ve done my bit. Billie, your swimsuit’s coming undone!’ She buttoned it up for her.

Billie had a tan, either permanently, or from the sun by the seaside where she had been before. As well as her brown skin, she had fawn-coloured eyes and, amazingly, blonde hair, real blonde . . . it didn’t seem to go with the rest of her. Billie’s mother was a . . . a what? From Pernambuco. No, her mother was German, she had lived in Pernambuco a long time with her German husband, and there must have been something once upon a time . . . Billie was, at a cautious guess, a half-caste, or a half-half-caste, something like that. There was a foreign sweetness about her; when she sat like that, with her legs drawn up, her hands behind her knees, she was like a beautiful cat. You could watch her forever.

‘What sort of schnaps was it we drank last night?’ Billie asked slowly, without taking her eyes off what was happening at a distance accessible only to herself. The question was perfectly valid – but her expression was wrong for it, a quietly dreamy rigidity, and then out came that question about schnaps . . . We laughed. She awoke. ‘Well . . .’ she said.

‘It was a Labommel schnaps,’ I said perfectly seriously.

‘No, really . . . what was it?’

‘It was a Swedish corn brandy. If you only have a glass of it as we did, it’s pleasant and refreshing.’

‘Yes, very pleasant . . .’ We were silent again, and enjoyed the sun. The wind breathed over us, fanning our skin and stroking our glowing pores. I was in a minority, but I didn’t mind. The two were united – not against me, but to some extent excluding me. For all our affection, as I walked along beside them, I suddenly felt that ancient childish feeling little boys sometimes have, that women are strange, alien beings whom you will never understand. The way they are made, what they have under their skirts . . . just the way they are! My boyhood coincided with a time when women’s rigging was something highly complicated – just think off all those hooks and buttons to be done up when they got dressed! Adultery must have been an intricate business then. Nowadays, men have more buttons than women, who, if they are clever, can open as simply as a zip-fastener. And sometimes, when I hear women talking together, I think each must know the secret of the other; they are subject to the same manipulations and fluctuations in their existence, they have children in the same way . . . People are always saying women hate each other. Perhaps it’s because they know each other so well? They know too much about one another, right down to their essential being, which for many of them is the same thing. The rest of us probably have a harder time of it.

There they were, sitting in the sun, chatting, and I felt content. It was rather like a eunuch’s contentment; if I’d been proud, I might have said a Pasha’s – but it wasn’t that at all. I felt so secure in their presence. Billie had been with us for four days, and in those four days we hadn’t had a single wrong moment together . . . it was all lightness and happiness.

‘What was he like?’ I heard the Princess ask. ‘The soles of his feet and the parting in his hair were a gentleman’s,’ said Sibylle, ‘but in between . . .’ I didn’t know whom they were talking about – I had just picked up the tail end.

‘Oh nonsense!’ said the Princess. ‘If a man is no good, you should leave him as fast as you can. As for that woman, she must be so stupid to stand for it. Oh well! Hey, look! Ssh! Sit quietly – then he’ll come nearer . . . Look at the way his tail bobs about!’ A little bird hopped up to us, inclined his head to one side, and then flew off, alarmed by something in his brain – we hadn’t moved.

‘What kind of bird was that?’ Billie asked.

‘That was a bulbulfinch,’ said the Princess.

‘Come on, silly – that wasn’t a bullfinch . . .’ said Billie.

‘I’ll tell you something,’ I lectured. ‘With those sort of answers it doesn’t matter if they’re right or not. They just have to be prompt! Jakopp told me once, how when their group went on an excursion, there was always one who was the information-wallah. He had to know everything. And when he was asked, What’s that building? He had to say, and quick, that’s the District Savings Bank of Lower Saxony! He didn’t have the faintest, but everyone was satisfied: the gap had been filled. That’s how it is.’

The girls smiled politely, and suddenly I was alone with my joke. Just a split second, then it was over. They got up.

‘Let’s have a race!’ said Billie. ‘Once round the meadow! Ready, steady – go!’

We ran. Billie led; she ran evenly, her well-trained body worked like a precise little machine . . . it was a joy to run with her. Behind me the Princess gasped occasionally. ‘Keep calm!’ I said to myself. ‘Breathe through your nose – use the whole of your foot – not too much spring!’ We ran on. Billie let out a long breath and stopped; we had gone almost once round the big meadow.

‘Whew!’ We were very hot. ‘The castle, and a shower!’ We took our bathing wraps and walked slowly over the meadow. I carried my gym shoes in my hand, and the grass tickled my feet. It’s good being with the girls, without any tension. Without tension?

2

‘What shall we take the child as a present?’

‘Sweets,’ suggested Billie.

‘No,’ I said, ‘the old woman won’t allow it–or she’ll have to share them out among the whole house.’

‘We’ll go and buy some buttons,’ said the Princess. ‘I’m sure I’ll find something. Come on, Billie! Forget about my hat!’ We went.

Frau Collin had written. She was very grateful to us, and we should go to Frau Adriani and talk with her, and then report back on the telephone. The expenses . . .

‘Not huddan! Ladi!’ shouted the Princess. Billie looked flummoxed, and I had to explain to her that that meant ‘left’ and ‘right’ – that was how they drove donkeys in Platt German. God knows how those old drovers’ calls originated.

Yes, the child, the ‘little thing’ . . . I reminded myself of how she was tormented and beaten, because of what was now imminent . . . As a boy, I had always suffered from a fear of thresholds, that wild fear of setting foot in a strange, completely unknown house. And when I finally went in, I was cowed and apprehensive, and naturally came a cropper. Animals smell fear. People smell fear. Things only improved when I learned that everybody has to die. But that took twenty years. The Platt German expresses the matter more pithily and with less pathos: ‘What’s he then? His bum’s only got two halves!’ Which is true.

And now I was a strange man going to a wicked, strange woman. I quickly played through the different scenarios of Hansel and the witch; ‘but I’m so shy’ . . . and then I recovered. It took much less time to happen than to write. It was over. A wise Indian said, ‘You have to kill the tiger in your mind, before the hunt–the rest is a formality.’ And Frau Adriani? I thought of my sergeant-major, and of the beaten, crying child . . . All right.

‘Shut up!’ the Princess shouted into a window where a parrot was squawking in his cage. ‘Shut up! Or you’ll be stuffed!’

The bird must have understood German, because it shut up.

Billie laughed. ‘You wanted to buy some Worcestershire sauce as well,’ she said, in one of those associations of ideas of which only women are capable.

‘Oh, yes! Come on, we’ll get it in Fructaffair, they’ve got everything.’

The Swedes spell some of their foreign words phonetically, which can be very funny. So we bought Worcestershire sauce. The Princess sniffed suspiciously at the stoppered bottle, and generally made the shop assistant’s life as hard as she possibly could; Billie knocked over a jar of gherkins, which survived the experience and escaped with a shock, foaming briefly in their vinegar . . .

‘Look, such a lot of salt!’ I said.

The Princess looked at the barrel, ‘As a child,

I always believed that a single drop of water in a salt warehouse would consume the entire stock.’

That made me think so hard, I almost forgot to follow the other two, who were already standing in the street, nibbling raisins. ‘We’ll find a doll for the child,’ said the Princess. ‘Come along! Oh no, wait – I’ll do it . . . no, Billie come with me!’

For a tiny instant, I felt sorry; I would have liked to stand on the pavement alone with Billie. What would we have said to each other? Nothing, of course.

‘Did you?’

‘We did,’ shouted Billie.

‘Let’s see it,’ I said.

‘But not on the street!’ she said.

‘D’you think the dolly will catch cold?’ said the Princess, and unwrapped the parcel. It was a Swedish girl, dressed in the national costume of Dalarne, bright and colourful. She was covered up again. ‘For it is more blessed to wrap than to receive,’ said the Princess, and tied the string. ‘Well then, let’s . . . Do you think she shoots, our dear lady?’

‘Just leave her to me . . .!’

‘No, I won’t, Poppa. You only come into it if she becomes abusive, and the fur starts flying. You do the introduction, and tell her that we’ve got the letter and everything, and then I’ll have it out with her.’

‘What about me?’ asked Billie.

‘You lie down in the woods in the meantime, Billie, we can’t possibly march up to the lady like an avenging army. Everything would be lost. Even two of us – it’s this way – is too many. Two against one – the one will start growling before we’ve even said anything . . .’

‘Well, you can hardly growl more than she does anyway. What a bitch!’ I had taken Billie’s arm.

‘Are you managing to do any work here?’ asked Billie.

‘Not likely!’ I said. ‘I’m pausing for inspiration . . . you’re a nice chap, Billie,’ I said quite out of the blue.

‘You young people,’ said the Princess, and made a face like a well-meaning aunt arranging an engagement, ‘I’m so glad you’re fond of each other!’

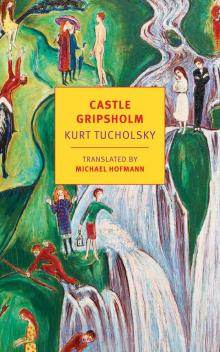

Castle Gripsholm

Castle Gripsholm