- Home

- Kurt Tucholsky

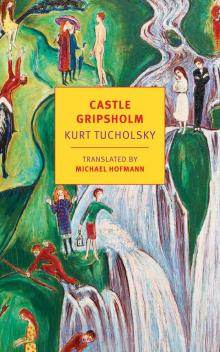

Castle Gripsholm Page 5

Castle Gripsholm Read online

Page 5

‘Everyone is to stay up here till the bell goes. No supper for anyone talking. Sonya! Your hair-ribbon!’ One of the girls went scarlet, took out of her hair a ribbon that had come undone, and tied it again. It was so quiet – you could hear forty little girls breathing. With a glare from her grey-green eyes, Frau Adriani took in the scene, then went out. Behind her back, a two-sided whispering started up: there were those who wanted to talk, very quietly, and the others who tried to stop them by going ‘Sshh!’ The child stood all by herself. Little girls can be very cruel. As no one else had been punished that day, the majority had tacitly decided that the child was to be ignored. The child was called ‘the child’ because once, in answer to Adriani’s question ‘What are you?’ she had replied ‘A child’. No one paid her any attention now.

When will this ever end? thought the child. It will never end. And then her tears flowed; she was crying just because she was crying.

2

The trees rustled outside the window, and they rustled me out of a dream. Even as I woke up, I had already forgotten what it was. I turned over on the pillows; they were still heavy with my dream. Forgetting . . . why had I woken up?

There was a knock.

‘The post! Poppa, it’s the post! Answer the door!’ The Princess, who the instant before had been asleep, was awake – there was no in-between.

I went. Between the bed and the door, I thought about these morning-moments between a man and a woman when love can be pretty dead. Critical moments, but if they pass, everything is all right. From the first croak of ‘What time is it . . .?’ to the ‘Huuargh – there, I’m getting up now!’ the little bedside clock ticks away a lot of time. The day has woken up, the night is asleep, the subterranean hemisphere is asleep . . . a pity, with the majority of women at least . . . I was at the door. A hand was pushing letters into the letter-box.

The Princess had half-sat up in bed, and in her excitement pillows were going everywhere. ‘My letters! Those are my letters! Give me them, you thief! Do I have to . . .’ She got her letter. It was from her replacement at work, and the news was that there was no news. The business with Tichauer had been sorted out all right. In the little inventory book they had reached G. I was most relieved to hear it. The worries of these people! What worries did they have? Their own, remarkably.

‘Go and heat up some water!’ said the Princess. ‘You need a shave. You’re in no state to kiss anyone looking like that. What was your letter about?’ I grinned and hid it behind my back. The Princess wrestled with the pillows. ‘Probably one of your women . . . one of those old Excellencies you adore so much . . . Show it here. Show it to me, I said!’ I didn’t.

‘I won’t show it to you!’ I said. ‘I’ll read you the beginning. I swear I’ll read it as it’s written, word for word. I swear. Then you can see it.’ A pillow fell out of bed, exhausted and battered to death.

‘Who’s it from?’

‘It’s from my Aunt Emmy. We had a quarrel. Now she wants me to do something for her. That’s why she’s writing. It says:

“My dear boy, Just before my cremation, I take up my quill . . .” ’

‘I don’t believe you!’ cried the Princess. ‘That’s . . . give it here! That’s rilly great, as Bengtsson would say. Now go and shave, and stop holding everybody up with your cremated aunts!’

Later we went out into the countryside.

Castle Gripsholm radiated into the sky; it was calm and solid and watchful. The lake rippled slightly and played against the shore. The boat to Stockholm had already gone; you could just make out a faint trace of smoke behind the trees. We headed in the opposite direction from the lake.

‘The lady at the castle,’ said the Princess, ‘speaks a sort of private German. She just asked me if we were warm enough at night – she was sure I was a little ice-cake . . .’

‘That’s lovely,’ I said. ‘You’re never sure with northerners whether they’re translating literally from their own language, or whether they’re unconsciously making up new phrases. In Copenhagen I knew a woman who said, in her furious bass voice, “This Copenhagen isn’t a capital city – it’s a capital hole!” Do you think she made that up?’

‘You know so many people, Poppa,’ said the Princess. ‘It must be nice . . .’

‘No, I don’t know nearly as many people as I used to. What’s the point?’

‘I’ll tell you something, my boy,’ said the Princess, who was really smitten with her Platt German today. ‘When you meet someone that you can’t quite make out, you should just ask yourself: will he give me love or money? If it’s neither, then let him go and don’t waste your time with him! All the same, is that any reason to tread in that cowpat!’

‘Damnation!’

‘You shouldn’t swear like that, Peter!’ the Princess said unctuously. ‘It’s not right. Let’s lie down for a while on that grass over there!’

We lay down . . .

The woods rustled. The wind blew through the tree-tops, and a delicate scent rose from the ground, fresh and sour, of moss and pine resin.

‘What would Arnold have said if he were here?’ I asked cautiously. Arnold was her ex; when the Princess was in a very good mood, one might risk reminding her of him. She was in a good mood now.

‘He wouldn’t have said anything,’ she answered. ‘He didn’t have anything to say anyway, but I only realised that much later.’

‘Not very quick then?’

‘There’s more sense in my wastepaper basket than there is in his head! He didn’t talk much. At first I thought his silences were terribly meaningful, but he just wasn’t much of a talker. You get them sometimes.’

A footfall on the soft moss; a little boy came stumbling along the forest path, muttering something to himself. When he saw us, he stopped, looked up at the trees and started running.

‘That could have been a case for the public prosecutor,’ I said. ‘With his ingenuity, he could have built up a whole case just from that. But the little boy was probably just reciting his tables, and felt embarrassed when he saw us . . .’

‘No, it was like this,’ said the Princess. She lay on her back and told her story to the clouds:

‘A boy was sent to the shops one day for soap and salt. So he kept singing to himself, soap and salt . . . soap and salt . . . But he didn’t watch where he was going, and he tripped over a string in a bean-field. Hell’s bells! A string and beans! String and beans! he said – and he stuck with string and beans, and ended up buying them. Oh, Peter! Peter! What’s life all about! Tell me quickly, what? I don’t want to hear any more foul language . . . I know all the words anyway. What is it about? I want to know right now!’

I sucked the end of a bitter fir-twig. ‘First of all,’ I said, ‘I saw how it was. And then I understood why it was like that – and then I appreciated why it couldn’t be any other way. But I still want it to be different. It’s a trial of strength. If you can remain true to yourself . . .’

In her deepest contralto voice she said, ‘After all the times you’ve proved how true you are to me . . .’

‘I wonder if it’s possible to have a serious conversation with a woman. I don’t think so. And they go and give the creatures a vote!’

‘That’s what my boss always says too. I wonder what he’s up to now?’

‘He’s probably bored, but really pleased with himself to be in Abbazia. Your Generalkonsul . . .’

‘Come on, Poppa, you’ve got your writer’s pride too. You know, sometimes I think the man has made it after all. He wasn’t born a Generalkonsul, with his soap and his safe and everything. He’s always telling me what a comfortable life he’s had – which means he hasn’t. He probably had a lot of lean years before they let him get at the cream. And now he’s licking his chops . . . What? Of course he’s forgotten the lean times. They all do. Memory, my boy, memory . . . it’s like an old barrel organ. Nowadays people have gramophones! If only you could find out what it’s like when someone makes it to the top – som

eone like my boss . . . He’s not married . . . but even if he was, his wife wouldn’t be able to tell you either, she wouldn’t have noticed anything. For her, success would be only natural, and people just don’t want to know about a hard grind to the top, because that would be admitting that their own ancestors were running around without a visor. Promotion . . . they just say that when they don’t want to give you a pay-rise.’ Thus spoke the sage Princess Lydia, and concluded her speech with a magnificent –

The Princess began to hiccough.

She wanted me to lift her up but with a beautifully athletic bound she stood up by herself. Slowly we crept back through the forest. We stopped at every little glade and made speeches, each of us pretending to listen to the other, and to admire the forest, and really doing both. But, if we’d been asked, we’d have had to confess that in our hearts, although we weren’t in Berlin anymore, we weren’t yet in Sweden. But we were together.

We passed the first house in Mariefred. A gramophone was scratching away.

‘It’s come here to convalesce,’ said the Princess in hushed tones. ‘You can hear it – it’s still quite hoarse. But the air here will do it the world of good.’

‘Are you hungry, Lydia?’

‘I’d like . . . Peter! Poppa! Oh, God! What’s the genitive of Smörgas . . . I’d like some Smörgassens . . . Oh blast!’ All this kept us occupied until we were sitting down at table, and the Princess had gone through the declension of the Swedish hors d’oeuvre.

‘What shall we do after lunch?’

‘What a question! After lunch we’re having a nap. Karlchen always says there’s such a lot of fatigue trapped in one’s day clothes . . . you have to take them off and have a proper rest. And you sleep. That restores your energy.’

‘Tell me, is your friend Karlchen still polishing his chair at that Revenue Office in the Rhineland?’

I said he was.

‘And what’s special about him, then?’

‘Now look,’ I said to the Princess, ‘he’s quite exceptional in every way! But one couldn’t tell him that because he would get so conceited, peacock feathers would sprout from his ears. He’s a . . . well, Karlchen’s just Karlchen!’

‘That’s no explanation. That’s just like my Konsul when there’s something he doesn’t want to say. I’m going to bed, to get some sleepas.’ I heard her singing to the tune of Tarara-boom-diay:

And then the little horse

suddenly turned about

and with a flick of his tail

he brushed away the flies –

The trees rustled in our sleep.

3

In the afternoon we stood in front of the castle – tourists were coming and going.

We walked around the castle garden; there was an ornate well in the middle and little oriel-windows jutted out from the walls. The castle had been renovated . . . a pity. But maybe the whole edifice would have fallen down otherwise. It was old enough.

A large tourer drove up.

A young man got out of it, then two ladies, one older, one younger, and finally a fat gentleman was scraped out of the back. They spoke German, and stood round their car looking perplexed, as if they had just arrived from the moon. The fat man spoke loudly and rapidly to the driver, who fortunately didn’t understand.

They bought tickets for the castle but the guide had already gone home, so they were left to do the pilgrimage on their own.

‘Lydia . . .’ I said. We set off after them.

‘What’s the plan?’ Lydia asked, lowering her voice. She had understood what I was thinking.

‘I’m not sure yet,’ I said, ‘I’ll think of something . . . Come along!’

The tourists were standing in the Great Hall, looking up at the panelled ceiling. One of the ladies said, so loudly that it echoed, ‘Not bad!’

‘Obviously Swedish style!’ observed the fat man. They muttered.

‘Now if they were to ask whether this was all built . . . Quick!’

‘Where to?’

‘To the big well. We’ll put on a performance for them there . . .’

We could hear them shuffling about and coughing – then we were out of earshot. We walked quietly and fast.

We came to the large round chamber with its wooden gallery. In the middle of the earthen floor was a circular wooden disc which was the entrance to the dungeons. We found a ladder. Lydia helped, and we dropped the ladder in. Hurray! It stood up! So the dungeon couldn’t be very deep. I climbed down, pursued by looks of mock admiration from the Princess. ‘Give my love to the bats!’

‘Shurrup!’ I said.

I went down – quite a long way . . . like an American film-comedian miming a fireman. That’s what it looked like, but I didn’t feel terribly amused. Where was I going? But I would do anything for a laugh. Only darkness and dust and the round beam of light from above . . . ‘Some matches please! From your handbag!’ The box came down and landed on my feet. I stooped and hit my head on the ladder – then I found it. A light . . . it was a large room. Rings had been set into one wall; evidently they didn’t correct their prisoners by easy stages, but all at once . . . There was a further well-hole, too.

‘Lydia?’

‘Yes?’

‘Pull the ladder up – can you manage? I’ll help you. I’ll lift it – har-rupp! There . . . have you got it?’ The ladder was back up. ‘Put it away!’ I heard the Princess moving the ladder away. ‘Put the cover back on, will you? And hide.’ Now it was completely dark. Black.

It’s strange, when you’re not used to it. The moment you find yourself in complete darkness, it feels inhabited. No, you expect it to be inhabited; you’re afraid of it, and so you long for some living presence. I cleared my throat gently, to show that I was still there, and had no hostile intentions . . . I groped in the darkness. There was a nail in the wall, I wanted to keep hold of that . . . Ah? There they were. You could hear their voices quite distinctly; the wooden disc was very thin.

‘There’s nothing here,’ said a voice. ‘Probably a well – for sieges and that sort of thing. Very interesting. Well, let’s go on. Nothing here.’

There will be, you wait.

‘Huuuuuuu!’ I wailed.

There was deathly quiet above. The dragging footsteps stopped.

‘What was that?’ someone asked. ‘Did you hear it?’

‘Yes, I thought so too – probably just a noise.’

‘Huuuuuuu-aa-huuuuuuu!’ I howled again.

‘For god’s sake Adolf, perhaps an animal has been shut in there, a dog, come along!’

‘Now really, I can’t believe it! Is – erhem – is someone down there?’

I kept very quiet.

‘An illusion,’ pronounced a man’s voice.

‘Come on! It wasn’t anything,’ said the other man.

I thought of the lions at the zoo before feeding-time, and drawing a deep breath I began to roar,

‘Huuuuuuu-brru-aa huuuuuuuuah!’

That was too much. One of the women shrieked, and then there was the noise of people legging it, but one still managed to say: ‘But it’s quite . . . there must be an explanation . . . we’ll ask at the gate . . . incredible . . . I mean it’s . . .’

‘Come along there! What do we have to go to all these castles for anyway . . .’

They were gone. I stood in my darkness, dead still.

‘Lydia?’ I whispered. No answer. Some dirt trickled down the wall. Hm . . . A sound? But everything here is wood and stone; there was no noise. I listened. My heart was pounding a little faster than I would have liked. Nothing. It’s wrong to give people a fright, you see, it’s wrong . . . ‘Lydia!’ Louder still, ‘Halloo! Hey! You!’ Nothing.

Thoughts flashed through my brain: it was just a joke. Served them right. Keep still, or you’ll get your clothes dirty. You’re scared. You’re not scared. It’s superstition. Lydia’s just coming. What if she’s fainted, or she’s died suddenly, then no one will know you’re down here. That only happ

ens in films. Pathé did something like that once. It’s cruel to lock people up in the dark. Once in the war, I saw someone released from a dark cell, the light made him giddy. Then he started crying. He hadn’t come up to scratch as a soldier, so they locked him away, that’s wrong. Give judges a taste of the sentences they dish out. But that won’t work, because they’ll know it’s just a taste. Hence the folly of the death sentence, when no one knows what it’s like. By now my heart was beating regularly, I was thinking, and letting my thoughts run on . . . The wooden cover moved; it was pushed aside. Light. Lydia. The ladder.

I climbed back up. The Princess was laughing her head off. ‘How did you get into such a state? Come over here – you’re going straight back to our rooms! God, what a sight!’

I was grey with dirt, festooned with spider’s webs, my hands were streaked with black and the rest of me was equally filthy.

‘What’d they say? What did you do? Oh boy, just take a look at your silly face in the mirror!’

I decided I’d rather not.

‘What kept you, woman? Leaves me languishing in a dungeon! That’s love for you!’

‘I . . .’ said the Princess, putting her mirror away again, ‘I was looking for a loo, but there wasn’t one. The old lords of the castle must have had chronic constipation!’

‘Wrong,’ I said donnishly. ‘Incorrect and uninformed. Of course they had certain localities for that purpose, which led into the moat, but when they were being besieged, well, then . . .’

‘It’s high time you had a wash now. You pig!’

We strolled over to our rooms, past the greatly astonished landlady, who must have thought I’d been drinking. I emerged, brushed and washed and with a fresh collar. I had been severely scrutinised by the Princess who had sent me back three times; each time she found more dirt.

Castle Gripsholm

Castle Gripsholm