- Home

- Kurt Tucholsky

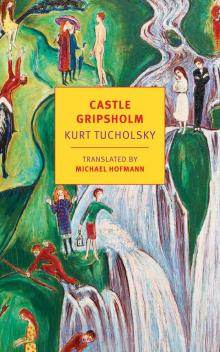

Castle Gripsholm Page 8

Castle Gripsholm Read online

Page 8

‘That’s where he gets all his culture from, Karlchen. Now would you get into an affair with your boss?’

Karlchen said he would never get into an affair with his boss.

‘It’s no good,’ the Princess said. ‘Men never understand. What would be the point? I’d have to share his worries like a wife, work like his secretary, and then, when he feels he’s safe, he’ll stop in the middle of somebody else’s room and ask her if she’s got a boyfriend . . . No thanks!’

‘And didn’t you think of me at all?’ I asked.

‘No,’ said the Princess, ‘I only start thinking of you if the man’s a possibility.’ We got up and walked down to the lake.

The castle slept, quiet and satisfied. Everywhere, there was a smell of water and of wood that had been lying too long in the sun, and of fish and ducks. We walked along the shore of the lake.

I enjoyed the other two; one was a friend. No, they were both friends – and I didn’t betray the woman for the man, as I had almost always done in the past; for when a man appeared, someone to talk to, then I dumped the woman, as though I hadn’t just slept with her; I gave her up, didn’t bother about her, and shamefully betrayed her to the first man who came along. Then she dropped me, and I wondered why.

The two of them were talking in their dialects about their respective regions. Where you had to pronounce the r and where not; they supplemented their stock of expletives; they both understood what lower German was about. Unfortunately, the German language hasn’t taken up its style: how much more expressive it is, more colourful, simpler and clearer – the best love-poetry in German has been written in it. And the people . . . the houses they had in old Lower Germany, particularly on the Baltic coast, were a dream-world of eccentricity, kindness and music, inhabited by an assortment of people like rare beetles, each one of them unique. A lot of its evocation has now fallen into the hands of stupid vernacular poets, may the devil take them, seemingly good-natured citizens with smoke-filled beards, brooding over steaming tankards, who have travestied the virility of their old language, and turned it into a deadly porridge of Gemütlichkeit: they are like head-foresters left in charge of the sea. Some have shaved off their beards and imagine they look like old woodcuts – but that doesn’t help; they can’t hear the woods or the sea, only their own beards rustling. Their good nature disappears the moment they turn confusedly to the present, and come up against political opposition; then the petit-bourgeois in them crawls out of the woodwork. Under their string vests, their hearts beat to the rhythm of a military parade.

That’s not our Platt German, not that.

But Lower Germany will never die – it lives and will go on living, as long as Germany exists. There has only ever been one comparable culture outside Germany, and that existed on the backs of an ill-treated, oppressed people: in Courland. The Lower German is a different animal. He chooses his words carefully and well. This was what the two of them were talking about. I knew that all the best things about the Princess came from that soil. In her I loved a part of this country which is usually so hard to love, and whose bewildered spirits think it a distinction to be hated. And there was Time again. No, I suppose there are no holidays for us.

The two of them chattered away non-stop. Each of them claimed their own version of Platt German as the only true and fair one, the other’s was entirely false. Now they had got around to telling stories.

The Princess told the one about the cobbler Hagen, to whom the administrator had called out his New Year’s greeting: ‘I wish you great happiness for the New Year, Master!’ Whereupon the other had yelled respectfully back across the market-square, ‘On the contrary, on the contrary, Herr Administrator!’ And the one about Mayor Hacher who had brought his ox along to the show, and said, ‘I’m not doing it for the money. I’m doing it for the disgrace!’

And then it was Karlchen’s turn again. He told how Dörte, Mathilde and Zophie, the nosiest girls in the whole town of Celle, had asked him who the young man was, who was to be found wandering about the streets every morning. And how he’d then woken them up at night, which was easy enough, as they lived on the ground floor, and when all three of them came to the window, considerably alarmed, he said: ‘I just wanted to tell you ladies that the morning visitor was a seller of holy books!’

And then they took it in turn to sing songs. The Princess sang:

‘Old Mother Pietsche sits on Mount Sinai,

and when she’s out of food, then she . . .

Karlchen, what about a little lullaby this afternoon?’ she asked suddenly. Karlchen was just singing:

‘She wore a brightly patterned dress,

and I’m still sore about the money I spent –

No,’ he said. ‘We’ll have a nice walk in the afternoon. It’ll do fatty here some good, and we’ll all sleep better at night.’

Fatty was me. He gazed at me benevolently. ‘Young people like you . . . you look so healthy and relaxed!’

That was how we felt too. I waddled along in silence beside them, because young love should be left to blossom.

Did he fancy her?

Of course he fancied her. But that was our unwritten law, our totem and taboo . . . We didn’t know what star we had been born under; but it must have been the same one. Each other’s women: never. We rationalised it like this: ‘Your taste in women – no thanks all the same!’ And again, for the hundredth time in as many years, I felt all the unspoken things in our friendship, the foundation on which it was built. I knew what made him tick. I knew it because I had seen all that the man had gone through (‘I’ve had my share of storms,’ he would say). I saw his unwavering self-control: when things went wrong he would keep a stiff upper lip. Often, when I was at a loss, I would ask myself what Karlchen would do. Then I’d be all right again for a time. A real male friendship . . . it’s like an iceberg: only the last quarter of it is visible above the surface. The rest is submerged and invisible. Fun – but fun is only good when there’s something serious behind it.

‘Preaching in Platt German,’ I heard Karlchen saying, ‘no-no.’

‘But that doesn’t make sense, Herr Karlchen,’ said the Princess. ‘Why not? The peasants understand it much better. Not your Platt, of course . . . but ours . . .!’

‘My beautiful young woman,’ Karlchen said, ‘that’s not the point. The peasants would understand it, and for that reason they wouldn’t like it. They don’t want to hear their everyday language in church; they have no respect for it – where’s the mystery in what they speak to their cows? They want the opposite, the formal, the unaccustomed. Otherwise they’ll be disappointed and won’t take the pastor seriously. There! And now we’re going to the Café Chantant – remember that, Fritzchen?’

How could I forget! That was Herr Petkov from Rumania, from the time we had both played in the Rumanian theatre of war. Herr Petkov used to tell stories that were distinguished by their singular pointlessness, but they always wound up in a brothel. ‘So he says to me: Petkov, you old bastard, let’s go to the Chantant!’ And what happened there, the Princess wanted to know.

Karlchen explained: ‘Petkov used to slap his thighs and say: here a girl and there a girl . . .’

‘Karlchen,’ said the Princess, ‘you’re making me blush!’

‘Petkov had a girlfriend too. She must have had a dozen lovers before him.’

‘A dozen lovers,’ said the Princess appraisingly, ‘and how many loose men?’

We walked along. The Princess stopped to powder her nose.

‘I can’t understand how you can powder your face in God’s own Nature,’ I said. ‘The fresh air . . . and your complexion is . . .’

‘Go and win the Nobel Prize and shut up!’ she said.

‘But listen, I’m serious . . .’

‘Poppa, it’s something men will never understand, and yet the two of us get along very well. Each to his own, cheri. You don’t use make-up, and I’m partial to a little powder. That’s how it is!’ We sat down on a

bench.

I growled, ‘They’re all the same . . .’ a sentence of Byron’s that made up half my entire stock of English.

‘Be nice to her for a change,’ said Karlchen. The Princess was delighted and gave him a friendly nod.

‘That’s right!’

‘Treat your bride as a woman, and your woman as a bride!’ said Karlchen.

‘Now give each other a kiss!’ I said.

They did.

‘Be nice to her!’ Karlchen said again. He was only passing through. Men in that position can always be clever and gentle, they have kind and wise words for every situation, and then they move on. But we who have to stay . . . But then that little cloud blew over. Because Karlchen quoted a good proverb to us:

‘At home they always say: It takes more than four bare legs in bed to make a marriage.’

‘Karlchen,’ I said abruptly, ‘what will become of us? I mean later . . . when we’re old . . .?’

He didn’t answer immediately. Instead it was the Princess who spoke: ‘Poppa, you remember what it said on the old clock we saw together in Lübeck, and which we couldn’t afford to buy just then?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘It said, Let the years speak for themselves.’

When we got home, we found a large bouquet for the Princess, of carrots, parsley and celery. It was from Karlchen, because that was how he showed his love.

2

‘Just wait till Frau Direktor sees that!’ said the maid Emma. ‘She’s already in a right temper today!’

The laughter of the four girls died on their lips. One bent down timidly to pick up the books they had just been throwing at one another. Hanne, fat Hanne from East Prussia, started to ask, ‘What is it? Is Frau Direktor . . .?’

‘Never mind!’ said the maid, with a malicious laugh. ‘You’ll see!’ And she hurried away. The four stood together a moment longer, then scattered hurriedly into the corridor. Hanne was last.

She had just opened the door of the dormitory where all the others were, collecting their bathing-things, when they heard Frau Adriani’s shrill voice from downstairs – how loud it must be, to be heard so clearly! The girls stood rigid like wax dolls.

‘Ha! So you didn’t know? Our little Lieschen didn’t know! Haven’t I told you a thousand times not to leave cupboards open? What? Ha?’ You could hear very soft, muffled crying. Upstairs the girls looked at each other and gasped; they thrilled with fear.

‘You’re a slut!’ said the distant voice. ‘A dirty slut! What? The cupboard opened by itself? Well I never . . . And what’s this? Eh? Since when have you been keeping food with your clothes? Eh? You limb of Satan! I’ll teach you . . .’

The crying grew louder; so loud, it could now be heard distinctly. They couldn’t hear any blows – Frau Adriani didn’t beat, she cuffed.

‘There – and there – and now . . . I’ll teach the pack of you . . .’ Fortissimo: ‘Everybody downstairs! Into the dining-hall!’

The wax dolls came to life; they threw their bathing-things onto their beds, their faces suddenly flushed, and one of them, pale Gertie, had tears in her eyes. Then there was another swift command, ‘Get along with you! Quick!’ and they went down-stairs, almost at a run, in silence.

The girls poured out of every door; they wore frightened expressions, one quietly asked, ‘What’s the matter . . .’ and was immediately silenced by the others; in a thunderstorm, it was best not to talk. Feet clattered down the stairs, doors banged . . . now the dining-hall was full. Last of all came Frau Adriani like a red cloud, with a crying Lisa Wedigen in tow.

The woman’s face was bright red. Only when she was in such a state of excitement was she fully alive.

‘Everybody present?’ She surveyed the assembled girls with a look that seemed to single out each girl as its object. Then she said harshly, ‘Lisa Wedigen has been stealing food!’

‘I . . .’ but the girl’s sobs choked what she was trying to say.

‘Lisa Wedigen is a thief. She has stolen our food,’ Frau Adriani said emphatically. ‘Stolen it, and then hidden it away in her cupboard. Of course the cupboard was in a disgraceful state, as always happens with thieves; her clothes were soiled with food, and the cupboard door was left open. So, as you clearly haven’t bothered to listen, I’ll have to make you understand. You remember what I told you at the beginning: if any of you misbehaves, you will all be punished for it. I’ll show you . . .! Right: Lisa will get no supper. For the next week she won’t be allowed to go on walks with the rest of us, she will have to stay in her room. Tomorrow she will get only half-helpings. Bathing has been cancelled today. You will all have writing-practice instead. And Lisa will copy out four chapters from the Bible. You’re an evil lot! Right, march – up to your rooms!’

In silence and with heavy hearts, the children trickled out through the two doors, some exchanged significant looks, the tougher ones swung their arms and acted defiant and unconcerned; two were crying. Lisa Wedigen was sobbing, she looked at no one and no one looked at her. The child looked up.

The big calendar-pad on the wall showed a 27, a black 27. As the child pushed through the doorway with the others, a draught leafed through the calendar . . . so many leaves, so many days. And when this calendar was used up, Frau Adriani would hang up another one. The child’s eye fell on the painting of Gustavus Adolphus in the corridor. He was all right. He was here and yet he wasn’t here. No one did anything to him. Strange, how people don’t hurt things. Another day like this, thought the child, and I’ll run away, away from this house . . .

There was quiet activity in the rooms. Bathing-costumes and towels were put away, trembling hands opened drawers and hastily rummaged about in them, the odd whisper was heard.

Down in the dining-hall, Frau Adriani stood alone.

She was breathing rapidly. To begin with she had coldly worked herself into a rage – for a pedagogical purpose, so she thought – and now she was purely and simply raging. Her fury only abated when she recalled her recent performance. She’d had such an attentive audience . . . everything depended on having an audience. She looked about herself. Everything here, down to the plaster on the walls, the putty in the window-frames, the lino floor and the door-hinges – everything was counted, checked, listed and supervised. There was nothing here that was not subject to her rule. She felt that if she glared at the fireplace, the fire would burn more quietly. This was her empire. It was for this reason that Frau Adriani didn’t like going out with the children; she spoiled their walks in any way she could, because nature wouldn’t stand to attention for her. Her will rampaged through the spacious villa, which had long ceased to be an ordinary house as far as she was concerned – it was her absolute domain, a world apart. Her world. She kneaded the children. Every day, she moulded her forty children, her servants, her nieces – her husband didn’t count. She played excruciatingly pleasurable games with these live figures, and continually checkmated them. Her will always prevailed. There was no secret behind her success: she believed in her victory, she could work like a carthorse, and she didn’t waste her emotions on others.

She thought she was unique, Frau Adriani. But she had brothers and sisters all over the world.

3

It was a bright summer’s day – and we were very glad. In the morning the clouds had dispersed quickly; now the wind dropped, and large white tufts of cotton wool gleamed high up in the blue sky, leaving at least half of it uncovered and dark-blue – and there was the sun, rejoicing.

‘We’re not having a nap today either,’ said Karlchen, who remarkably didn’t want to sleep after lunch. ‘Instead we’ll go for a walk in the fields. Right!’

Away we went. Peasants passed us, we greeted them, and they answered something we didn’t understand.

‘Don’t learn the Swedish for everything!’ said the Princess. ‘If you speak a foreign language perfectly, then it stops being so much fun. The Tree of Knowledge isn’t always the Tree of Life.’

‘Lydia,’ I said, ‘let’s

go past the children’s home this time!’

We did.

Down the avenue and round the lake. Once a car came reeling towards us, there was no other way of putting it, it was moving in a zig-zag.

A young man was at the wheel, with that silly, strained expression of learner-driver. His teacher sat next to him. We leapt out of the way, because the young man would have run over the three of us as easily as running over an ant . . . We left the avenue and turned into the wood.

In Sweden, paths sometimes take you directly through small properties, a gate is left open, and you pass through the yard. There were little cottages, quiet and clean . . .

‘Look – that’ll be the children’s home over there!’ said Karlchen.

On a little hill was a long house-front; that was it. Slowly we approached it. Everything was very peaceful. We stopped.

‘Tired?’ We lay down on the moss and rested. A long, long time.

Suddenly a door slammed in the house – it was like a pistol shot. Quiet. The Princess raised her head.

‘I wonder if we’ll get to see their strict teacher . . .’ I didn’t finish my sentence. A small door had opened at the side of the house, and a little girl flew out. She was running blind. No, like an animal; she didn’t need to look where she was going–she was driven by instinct. First of all, she ran straight ahead, then she looked up, and with a lightning movement, she swerved and ran straight into our arms.

‘There . . . there,’ I went.

The child looked up: as if waking from a long sleep. Her mouth opened and closed again, her lips trembled, she didn’t speak. Now I recognised her: we had met her with the others on our walk.

‘Well . . .?’ said the Princess. ‘You are in a hurry . . . where are you off to. Playing?’

At that, the little girl’s head dropped, and she began to cry . . . I had never heard anything like it. Women are less lyrical than we men are, when confronted with pain, so they are more helpful.

The Princess bent over her. ‘What is it . . . what’s the matter?’ and wiped her tears away. ‘What is it? Who’s hurt you?’

Castle Gripsholm

Castle Gripsholm